This edition of Print, America’s Graphic Design Magazine, fea- tured the creative work of Muir Coirnelius Moore the year after it became the fastest growing advertising agency on the US east coast, when it applied the principals of what is now known as Integrated Marketing Communication to support IBM in their launch of the PC, overtaking Apple in market share.

They sometimes use the initials MCM, which on a cornerstone would suggest the turn of the century: 1900. But in appearance, in style and in manner they are elaborately, aggressively 20th Century. Looking forward to 21.

They are also, quite possibly, among the most committed and successful practitioners in a new breed of communications service businesses, which evade and even contradict the classic structures and organizations.

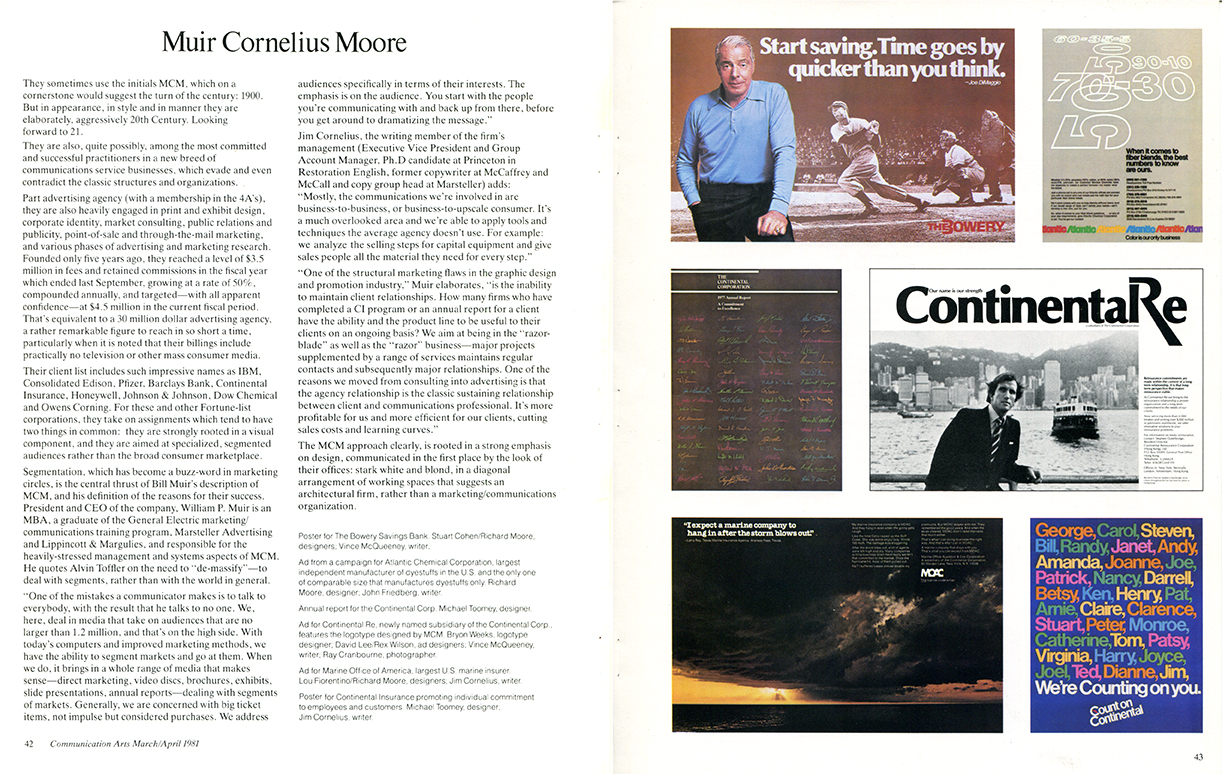

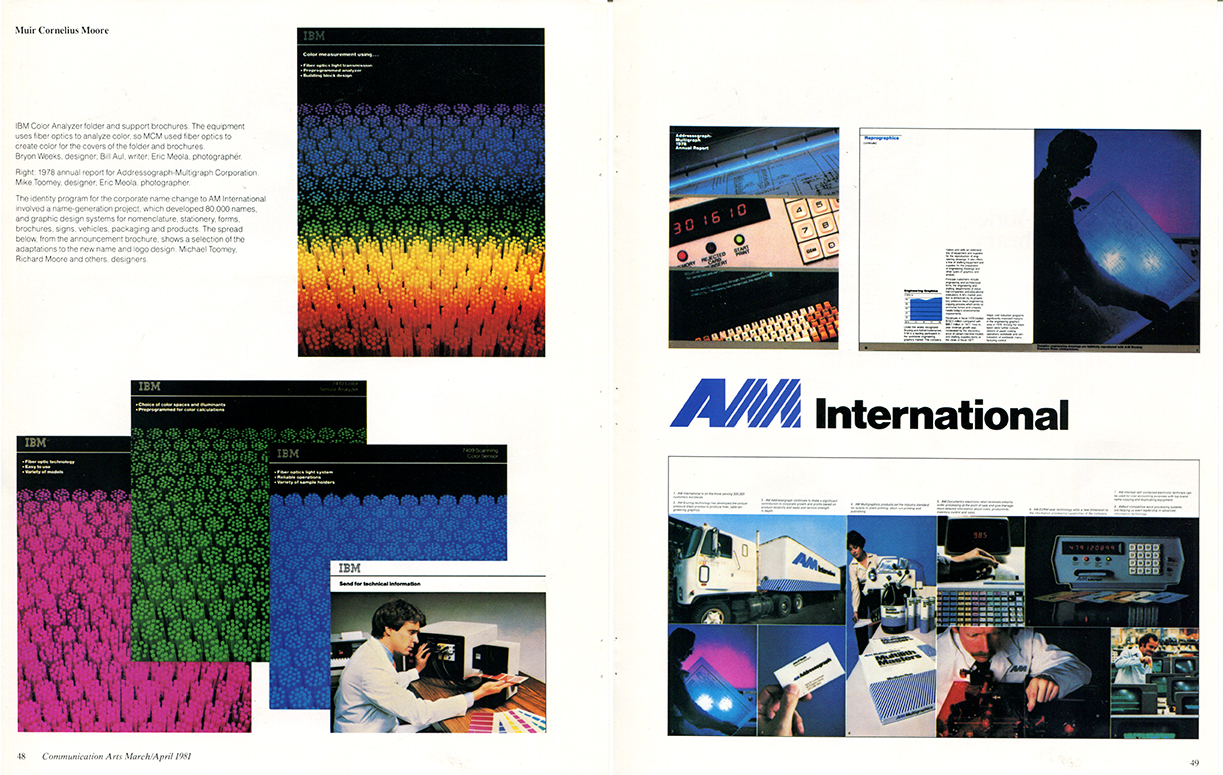

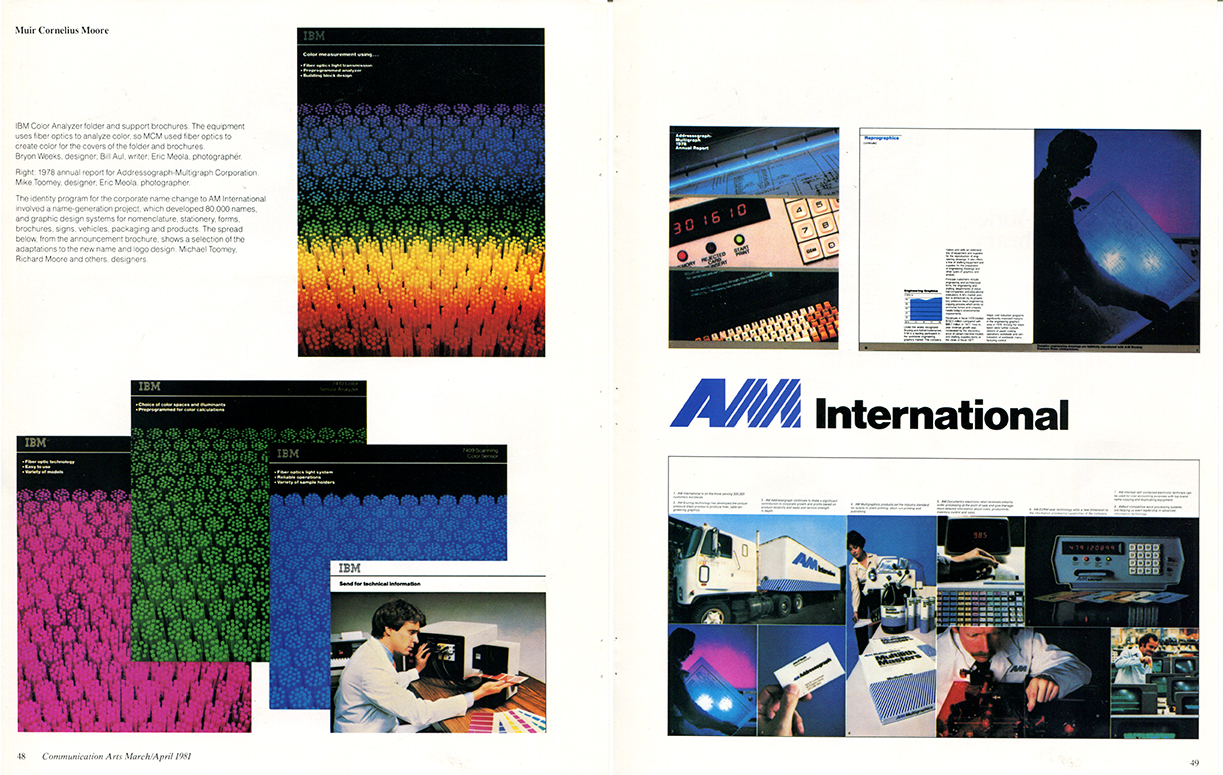

Part advertising agency (with a membership in the 4A's) , they are also heavily engaged in print and exhibit design, corporate identity, market consulting, public relations and publicity, point-of-sale and through-the-mail marketing, and various phases of advertising and marketing research. Founded only five years ago, they reached a level of $3.5 million in fees and retained commissions in the fiscal year which ended last September, growing at a rate of 50% , compounded annually, and targeted—with all apparent confidence—at $4.5 million in the current fiscal period. That's equivalent to a 30 million dollar advertising agency, a rather remarkable figure to reach in so short a time, particularly when it is noted that their billings include practically no television or other mass consumer media.

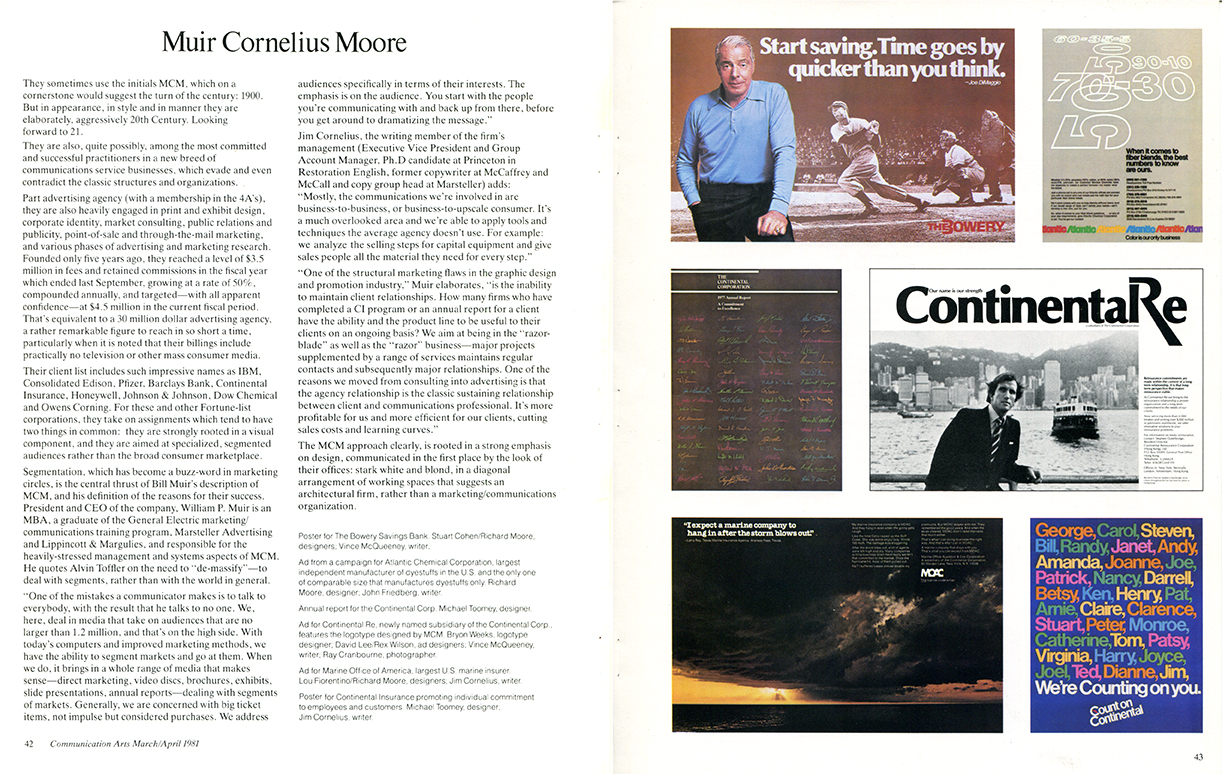

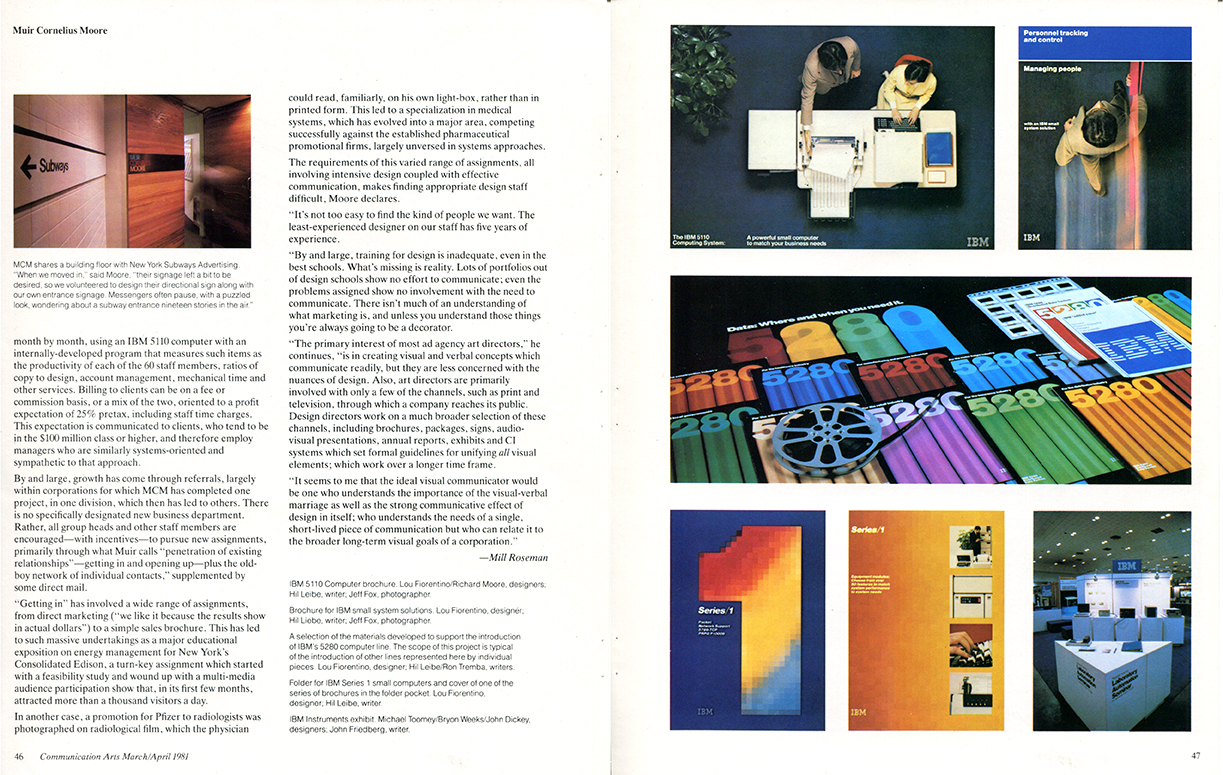

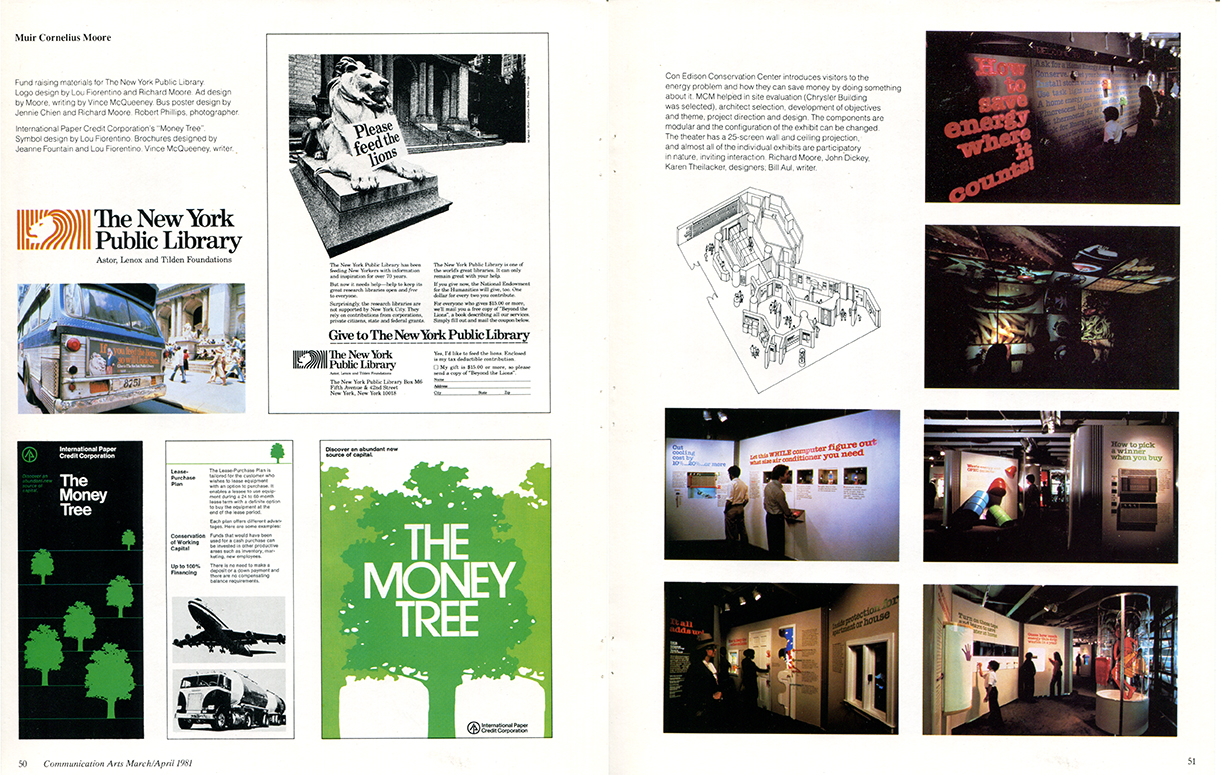

Their client list includes such impressive names as IBM, Consolidated Edison, Pfizer, Barclays Bank, Continental Insurance, Honeywell, Johnson & Johnson, Dow Chemical and Owens Corning. For these and other Fortune-list corporations, they take on assignments which tend to have two things in common: they are strongly rooted in a visual component, and they are aimed at specialized, segmented audiences rather than the broad consumer marketplace.

Segmentation, which has become a buzz-word in marketing circles, is the central thrust of Bill Muir's description of MCM, and his definition of the reasons for their success. President and CEO of the company, William P. Muir is an MBA, a graduate of the General Electric marketing/ communications training program, Marsteller Advertising and Lippincott & Margulies, and responsible for the heavily-stressed management and systems aspects of MCM. He quotes Alvin Toffler on the need to “de-massify—to deal with segments, rather than with the world in general."

"One of the mistakes a communicator makes is to talk to everybody, with the result that he talks to no one. We, here, deal in media that take on audiences that are no larger than 1.2 million, and that's on the high side. With today's computers and improved marketing methods, we have the ability to segment markets and go at them. When we do, it brings in a whole range of media that makes sense—direct marketing, video discs, brochures, exhibits, slide presentations, annual reports—dealing with segments of markets. Generally, we are concerned with big ticket items, not impulse but considered purchases. We address audiences specifically in terms of their interests. The emphasis is on the audience. You start with the people you're communicating with and back up from there, before you get around to dramatizing the message."

Jim Cornelius, the writing member of the firm's management (Executive Vice President and Group Account Manager, Ph.D candidate at Princeton in Restoration English, former copywriter at McCaffrey and McCall and copy group head at Marsteller) adds: "Mostly, the communications we're involved in are business-to-business, or business-to-upscale consumer. It's a much overlooked area and we're able to apply tools and techniques the average agency doesn't use. For example: we analyze the selling steps for capital equipment and give sales people all the material they need for every step."

"One of the structural marketing flaws in the graphic design and promotion industry," Muir elaborates, "is the inability to maintain client relationships. How many firms who have completed a CI program or an annual report for a client have the ability and the product line to be useful to their clients on an ongoing basis? We aim at being in the “razor-blade" as well as the "razor" business—major projects supplemented by a range of services maintains regular contacts and subsequently major relationships. One of the reasons we moved from consulting into advertising is that the agency relationship is the classic sustaining relationship between client and communications professional. It's more profitable for us and more efficient for our clients, cutting sales costs and learning curves."

The MCM approach clearly, is rooted in a strong emphasis on design, communicated in the first place by the look of their offices: stark white and blond, in a diagonal arrangement of working spaces that suggests an architectural firm, rather than a marketing/ communications organization.

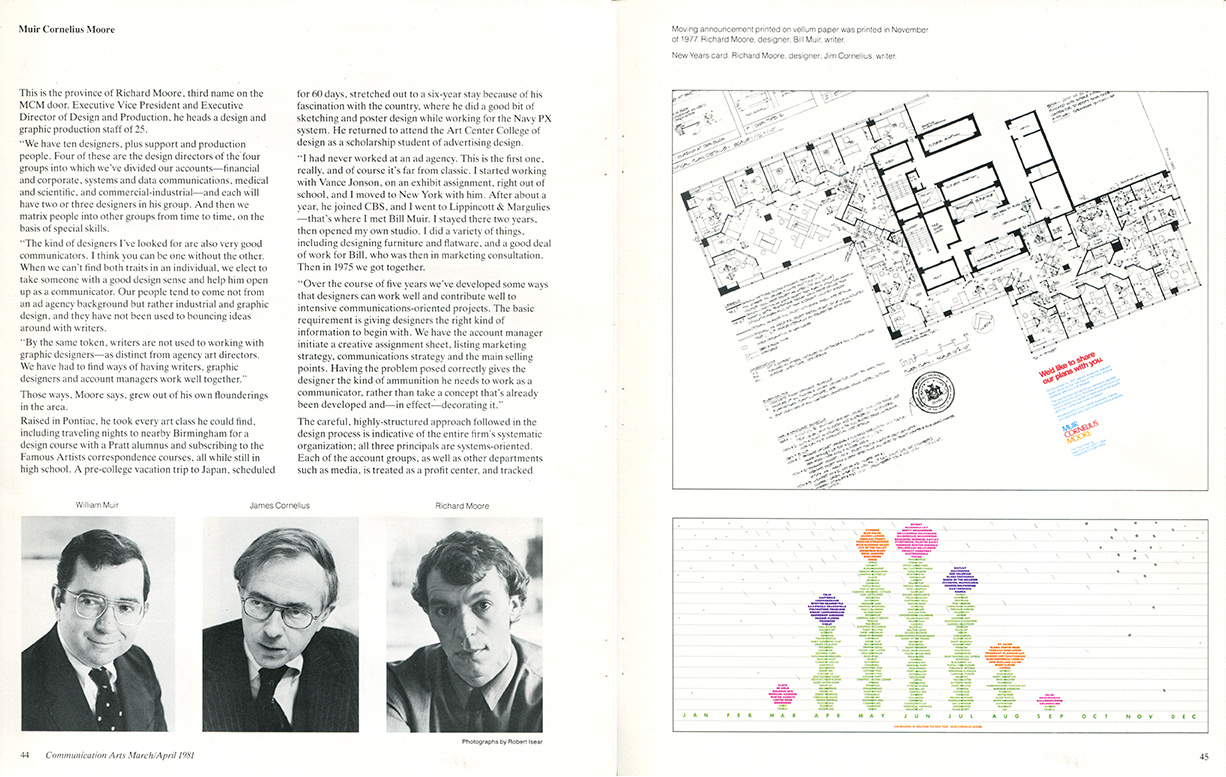

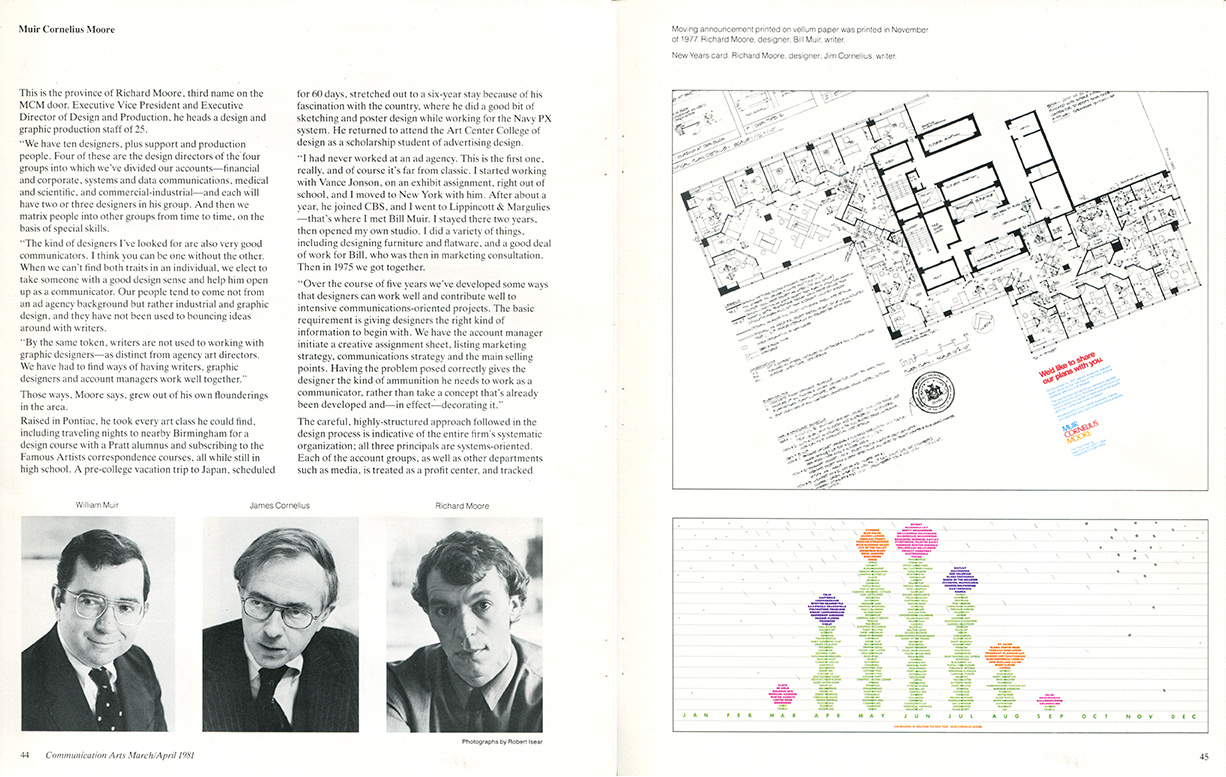

This is the province of Richard Moore, third name on the MCM door. Executive Vice President and Executive Director of Design and Production, he heads a design and graphic production staff of 25.

"We have ten designers, plus support and production people. Four of these are the design directors of the four groups into which we've divided our accounts—financial and corporate, systems and data communications, medical and scientific, and commercial-industrial—and each will have two or three designers in his group. And then we matrix people into other groups from time to time, on the basis of special skills.”

"The kind of designers I've looked for are also very good communicators. I think you can be one without the other. When we can't find both traits in an individual, we elect to take someone with a good design sense and help him open up as a communicator. Our people tend to come not from an ad agency background but rather industrial and graphic design, and they have not been used to bouncing ideas around with writers.”

"By the same token, writers are not used to working with graphic designers—as distinct from agency art directors. We have had to find ways of having writers, graphic designers and account managers work well together." Those ways, Moore says, grew out of his own flounderings in the area.

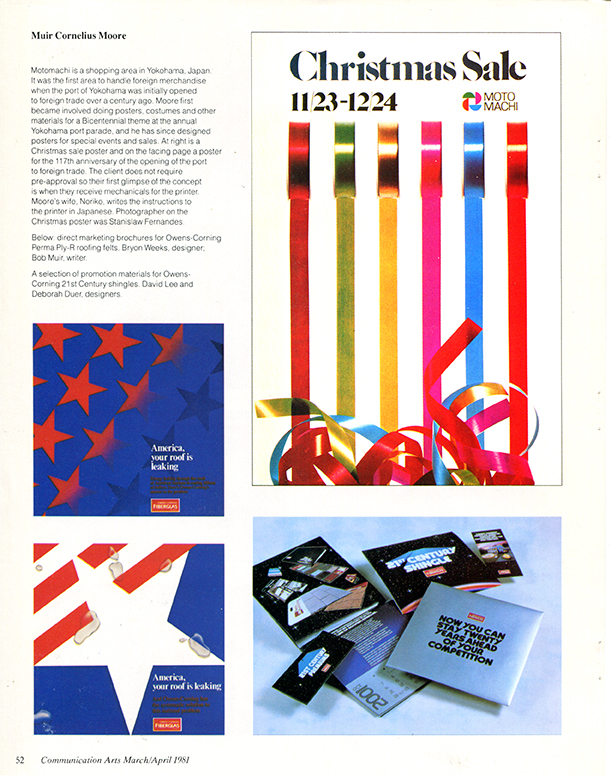

Raised in Pontiac, he took every art class he could find, including traveling nights to nearby Birmingham for a design course with a Pratt alumnus and subscribing to the Famous Artists correspondence courses, all while still in high school. A pre-college vacation trip to Japan, scheduled for 60 days. stretched out a six-year stay because of his fascination with the country, where he did a good bit of sketching and poster design while working for the Navy PX system. He returned to attend the Art Center College of design as a scholarship student of advertising design.

"I had never worked at an ad agency. This is the first one, really, and of course it's far from classic. I started working with Vance Jonson, on an exhibit assignment, right out of school, and I moved to New York with him. After about a year, he joined CBS, and I went to Lippincott & Margulies —that's where I met Bill Muir. I stayed there two years, then opened my own studio. I did a variety of things, including designing furniture and flatware, and a good deal of work for Bill, who was then in marketing consultation. Then in 1975 we got together.”

"Over the course of five years we've developed some ways that designers can work well and contribute well to intensive communications-oriented projects. The basic requirement is giving designers the right kind of information to begin with. We have the account manager initiate a creative assignment sheet, listing marketing strategy, communications strategy and the main selling points. Having the problem posed correctly gives the designer the kind of ammunition he needs to work as a communicator, rather than take a concept that's already been developed and—in effect—decorating it."

By and large, growth has come through referrals, largely within corporations for which MCM has completed one project, in one division, which then has led to others. There is no specifically designated new business department. Rather, all group heads and other staff members are encouraged—with incentives—to pursue new assignments, primarily through what Muir calls "penetration of existing relationships"—getting in and opening up—plus the old-boy network of individual contacts," supplemented by some direct mail.

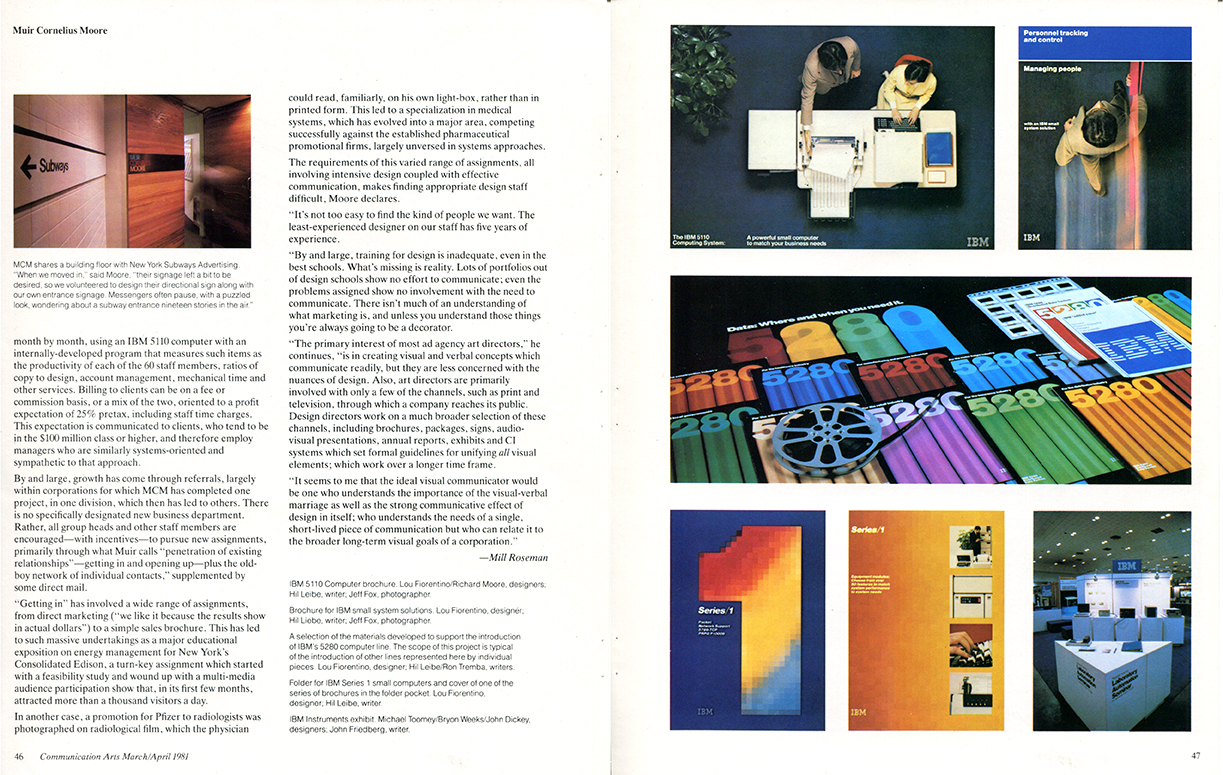

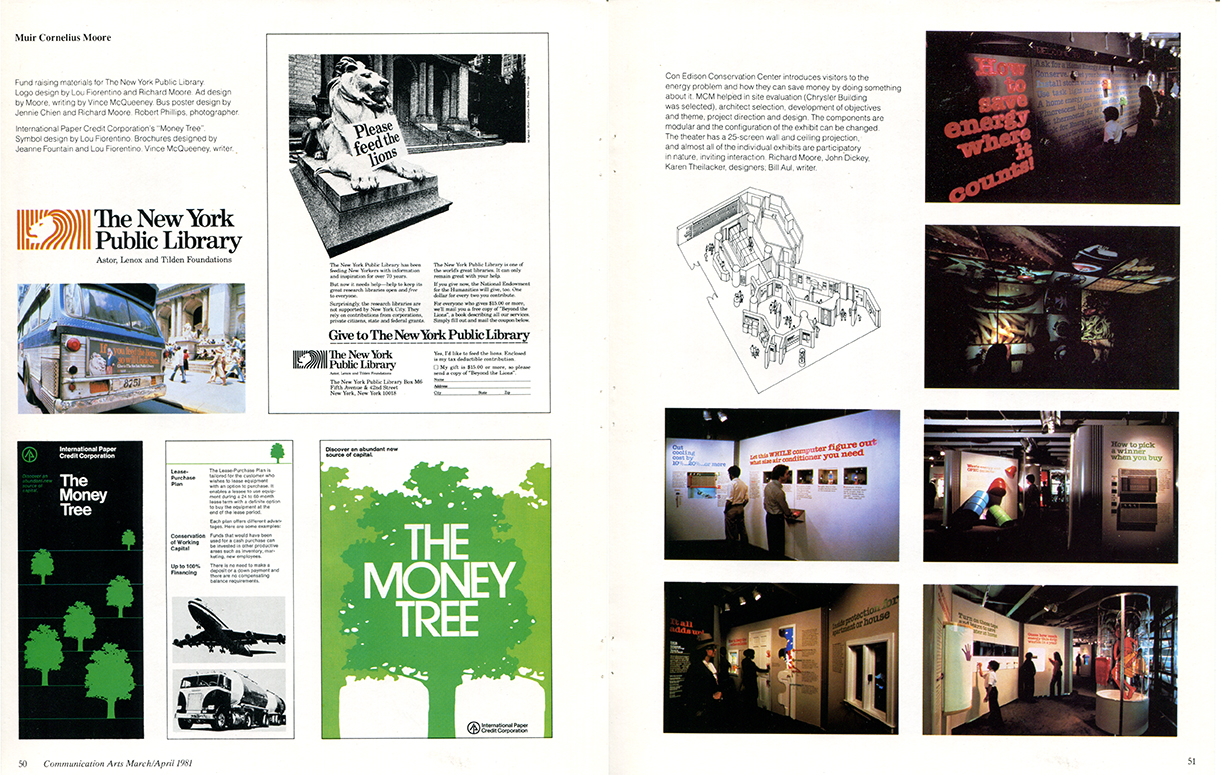

"Getting in" has involved a wide range of assignments, from direct marketing ("we like it because the results show in actual dollars") to a simple sales brochure. This has led to such massive undertakings as a major educational exposition on energy management for New York's Consolidated Edison, a turn-key assignment which started with a feasibility study and wound up with a multi-media audience participation show that, in its first few months, attracted more than a thousand visitors a day.

The requirements of this varied range of assignments, all involving intensive design coupled with effective communication, makes finding appropriate design staff difficult, Moore declares.

"It's not too easy to find the kind of people we want. The least-experienced designer on our staff has five years of experience.”

"By and large, training for design is inadequate, even in the best schools. What's missing is reality. Lots of portfolios out of design schools show no effort to communicate; even the problems assigned show no involvement with the need to communicate. There isn't much of an understanding of what marketing is, and unless you understand those things you're always going to be a decorator.”

"The primary interest of most ad agency art directors," he continues, "is in creating visual and verbal concepts which communicate readily, but they are less concerned with the nuances of design. Also, art directors are primarily involved with only a few of the channels, such as print and television, through which a company reaches its public. Design directors work on a much broader selection of these channels, including brochures, packages, signs, audiovisual presentations, annual reports, exhibits and CI systems which set formal guidelines for unifying all visual elements; which work over a longer time frame.”

"It seems to me that the ideal visual communicator would be one who understands the importance of the visual-verbal marriage as well as the strong communicative effect of design in itself; who understands the needs of a single, short-lived piece of communication but who can relate it to the broader long-term visual goals of a corporation."—Mill Roseman.