This edition of Art Direction, The Magazine of Visual Communi- cation, was published after Muir Cornelius Moore merged into Interpublic, then the world’s largest advertising conglomerate, and was renamed Lintas: MCM. The article likens good creative to good mountaineering and describes some of Richard’s alpine experiences.

RICHARD MOORE, CHIEF CREATIVE OFFICER (and final 'M') of Lintas: MCM, likens good creative to good mountaineering: "Best at the edge—taking risks—but risks within your ability to control." Richard's been much awarded for his sales promotion and corporate identity work for blue chip clients like IBM. He also climbs mountains.

Richard began climbing nearly 30 years ago in Japan, where he took off on a "60 day" trip before college. While there, he got a job with the U.S. Navy PX System. "Half my responsibility was posters, newsletters and Starts & Stripes press releases promoting the PX. The other was making bi-weekly drives to a mobile, Marine PX at the base of Mt. Fuji." To a kid from Michigan, those rides—weaving across the countryside's "immense" foothills on little, narrow roads—seemed full of mystery. Richard stayed at the job 6 years. When he did eventually return he brought back a Japanese fiancée, a design portfolio, and a love of mountain climbing.

He started out hiking in the mountains that hug Japan's coastline. That led to rock climbing, and—perhaps because he was the only foreigner then active in the sport—an introduction to one of Japan's most prestigious climbing organizations, the Japan Climbers Club. "I didn't realize at the time how unusual it was to have been admitted. I only knew that these guys were serious. Many of the first ascents in the Japan Alps had been made by the club's members and everyone had to spend at least thirty days a year in the mountains." Their enthusiasm spurred Richard on, and though he's no longer a member, he still keeps in touch with the twenty-odd climbers he met there.

Back in the U.S., Richard continued to climb during one and two-week semester breaks from the Art Center College of Design, and when he moved to New York he kept in shape at a popular rock face near New Paltz. But as his design work grew, the opportunities to take off for peaks unknown came less and less frequently.

Then, on New Year's Day 1975, a year before cofounding Muir Cornelius Moore, Richard was awakened with a call from Japan, inviting him to join an expedition on the west face of Peak 29, one of the biggest unclimbed faces in the Nepalese Himalayas. "How," he asks, "could I start the year saying ‘no'?"

"It was a first attempt over unexplored terrain," Richard recalls, "and the expedition eventually ran out of time, food and luck. The ridge route above high camp was getting bombarded with rockfall where it met the overhanging face above. On one of the last days at high altitude the monsoon set in and the weather deteriorated. We found ourselves inside a storm. The air was so charged with electricity I could feel my ice axe vibrating.

"The route hasn't been climbed since, although at least two climbers have died trying." During the trip, Richard discovered another, somewhat less extreme, dimension to mountain travel. "I joined a foraging party to bolster our dwindling supply of provisions and learned the pleasures of trekking from village to village in the shadows of peaks over 20,000 feet.”

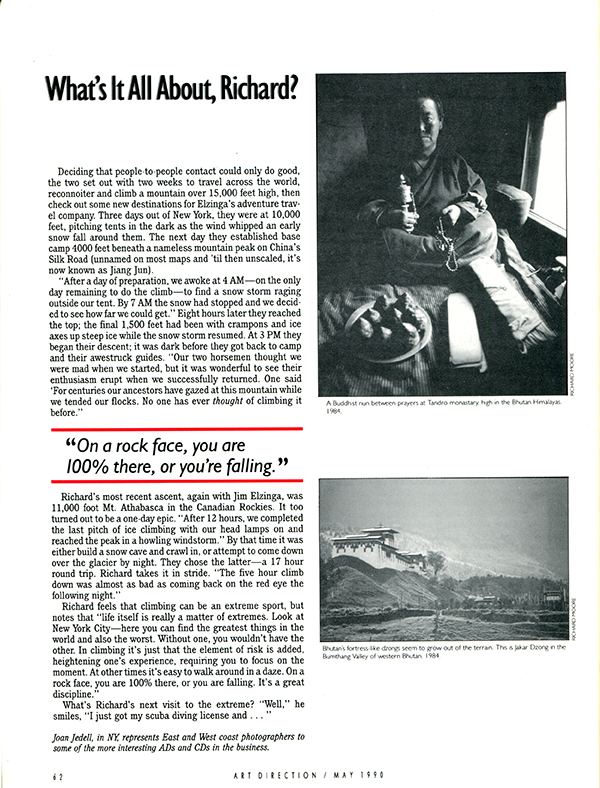

While in Nepal, Richard heard of the neighboring kingdom of Bhutan. And when later he learned of a couple planning a trekking traverse of the Himalayas, he joined them for the Bhutan segment—one of the first treks permitted in this remote Buddhist kingdom. "My photography of the trip was shown at the Overseas Press Club and a travel article was published. The Ministry of Tourism heard of it and, much to my surprise, I was invited back as a guest of the Royal Government." Two subsequent trips have led to a tourism video and promotional literature, with the design, outline, and most of the photography created and approved while trekking with Bhutan's Manager of Tourism. Talk about mixing business and pleasure!

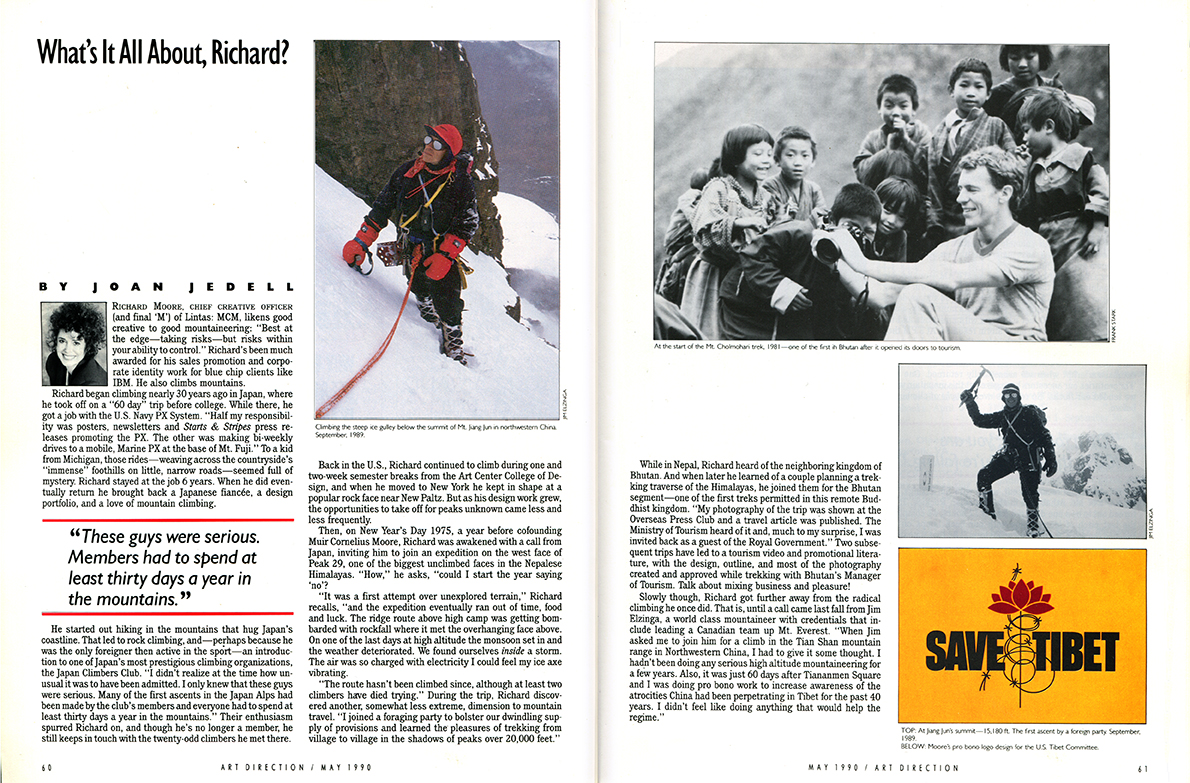

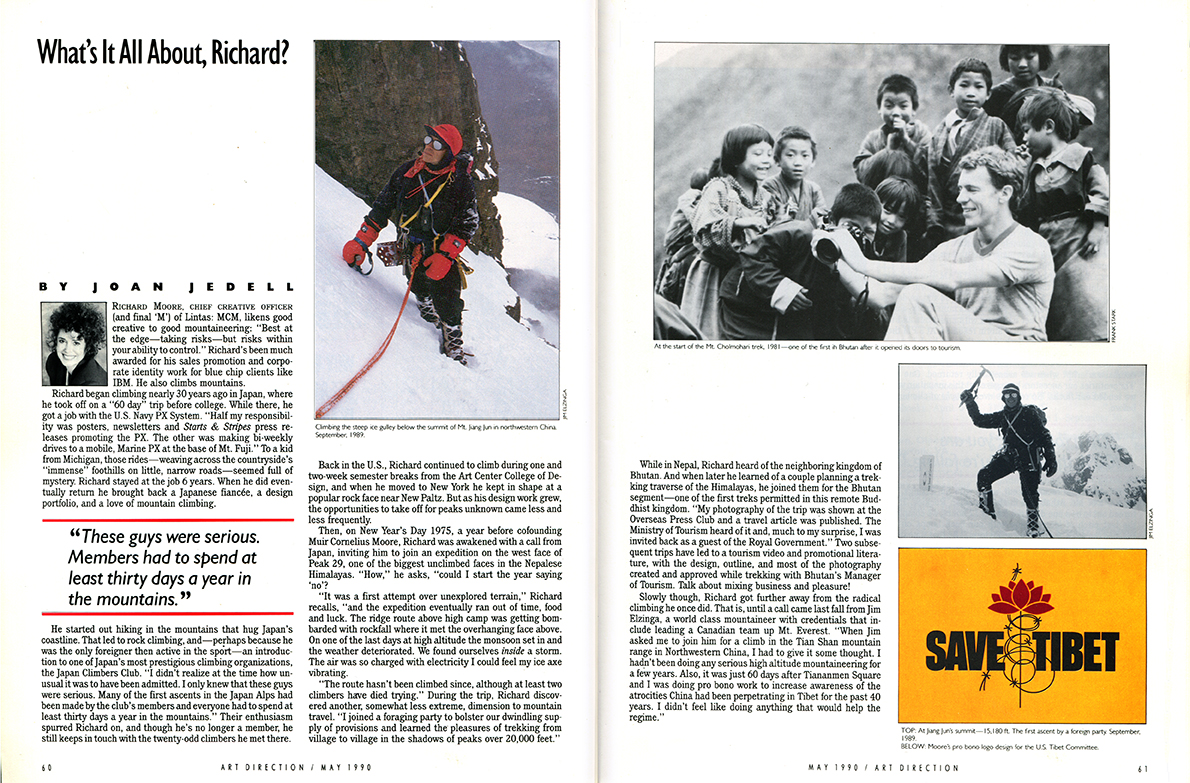

Slowly though, Richard got further away from the radical climbing he once did. That is, until a call came last fall from Jim Elzinga, a world class mountaineer with credentials that include leading a Canadian team up Mt. Everest. "When Jim asked me to join him for a climb in the Tian Shan mountain range in Northwestern China, I had to give it some thought. I hadn't been doing any serious high altitude mountaineering for a few years. Also, it was just 60 days after Tiananmen Square and I was doing pro bono work to increase awareness of the atrocities China had been perpetrating in Tibet for the past 40 years. I didn't feel like doing anything that would help the regime."

Deciding that people-to-people contact could only do good, the two set out with two weeks to travel across the world, reconnoiter and climb a mountain over 15,000 feet high, then check out some new destinations for Elzinga's adventure travel company. Three days out of New York, they were at 10,000 feet, pitching tents in the dark as the wind whipped an early snow fall around them. The next day they established base camp 4000 feet beneath a nameless mountain peak on China's Silk Road (unnamed on most maps and 'til then unscaled, it's now known as Jiang Jun).

"After a day of preparation, we awoke at 4 AM—on the only day remaining to do the climb—to find a snow storm raging outside our tent. By 7 AM the snow had stopped and we decided to see how far we could get." Eight hours later they reached the top; the final 1,500 feet had been with crampons and ice axes up steep ice while the snow storm resumed. At 3 PM they began their descent; it was dark before they got back to camp and their awestruck glides. "Our two horsemen thought we were mad when we started, but it was wonderful to see their enthusiasm erupt when we successfully returned. One said 'For centuries our ancestors have gazed at this mountain while we tended our flocks. No one has ever thought of climbing it before."

Richard's most recent ascent, again with Jim Elzinga, was 11,000 foot Mt. Athabasca in the Canadian Rockies. It too turned out to be a one-day epic. "After 12 hours, we completed the last pitch of ice climbing with our head lamps on and reached the peak in a howling windstorm." By that time it was either build a snow cave and crawl in, or attempt to come down over the glacier by night. They chose the latter—a 17 hour round trip. Richard takes it in stride. "The five hour climb down was almost as bad as coming back on the red eye the following night."

Richard feels that climbing can be an extreme sport, but notes that "life itself is really a matter of extremes. Look at New York City—here you can find the greatest things in the world and also the worst. Without one, you wouldn't have the other. In climbing it's just that the element of risk is added, heightening one's experience, requiring you to focus on the moment. At other times it's easy to walk around in a daze. On a rock face, you are 100% there, or you are falling. It's a great discipline."

What's Richard's next visit to the extreme? "Well," he smiles, "I just got my scuba diving license and…”